The role of education in social inequalities is difficult to assess, because it seems to have contradictory tendencies. On the one hand, improving access to education at all levels -- from elementary school to graduate school -- levels the playing field because it enhances the ability of everyone affected to realize their human talents and to pursue their goals with a greater foundation of cognitive and mental skills. Closing the literacy gap, the numeracy gap, or the technology gap across all of society gives the previously disadvantaged population a better chance to compete for success in seeking employment or creating other economic and social benefits for themselves and their families. Traditional sources of social inequality -- positions of privilege in social hierarchies, privileged access to political benefits, disproportionate ownership of land and other forms of productive property -- are to some extent blunted by a greater degree of equality of access to good schooling and the knowledge and skills it provides. So we might say that improving the quality and reach of a society's educational system should be expected to reduce existing inequalities.

On the other hand, access to education amplifies everyone's talents -- elite and disadvantaged alike. And more importantly, education proceeds through specific, concrete social institutions -- schools and universities -- and the quality and effectiveness of these educational institutions varies enormously across the face of a complex society. It is possible -- perhaps likely -- that these variations in quality will correspond to populations and neighborhoods in ways that align with patterns of prior advantage and disadvantage. So it is likely that we will have high-quality, effective schools providing education to advantaged groups; and low-quality drop-out factories providing education to the disadvantaged institutions. In this case, the education system might actually have the effect of deepening and entrenching the social inequalities that exist across groups.

I've put this point in hypothetical terms. But we know that across much of the United States, this isn't simply a hypothetically possibility. It is largely a fact on the American cityscape that schools vary in quality by race, poverty, and social status at the K-12 level. Affluent people are often served by good public schools, and they have the financial ability to choose good private schools if they are unsatisfied. Poor people are usually served by schools with severe disadvantages -- under-resourced, dilapidated, endemic management crisis, disaffected teachers and principals. So it is hard to make the case that American public education is a powerful force for decreasing social inequalities.

So what about American universities? Here the picture is more favorable. High school graduates who have gained the intellectual abilities required for succeeding at the university level -- admittedly, often a minority of all graduates -- have a range of choices that can genuinely erase most of the disadvantages of birth. A first-generation freshman from a low-income family can nonetheless gain a great engineering education or a great education in art history at an affordable public university; and this undergraduate success in turn positions him or her for future successes in graduate school or employment. So American universities do in fact deliver much of the promise of the theory of democratic education: broad access without regard to status or income, and substantial enhancement of life prospects as a result.

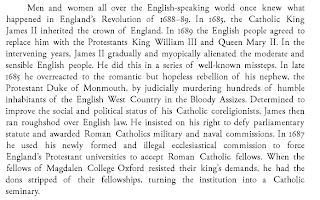

That said, American universities continue to reproduce a more specific form of elite advantage. Here is a January 2011

Newsweek review of America's elites and their university degrees. The snapshot it provides is a familiar one; elite positions in our society are disproportionately held by graduates of elite universities. Think of the number of US presidents and members of Congress with Ivy League degrees. Plainly our political elite was disproportionately produced by an elite set of universities (

link). But similar results seem to obtain in the business world as well. The same

Newsweek story reports that elite universities also produced the largest bloc of CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, with Harvard, Columbia, and the University of Pennsylvania leading the list, and Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio State providing a significant number of CEOs as well. Put the point this way: entry into an elite university greatly increases an individual's likelihood of becoming a member of the political and business elites in America. It is true, of course, that talented young people attend these universities, and it is predictable that they will be successful. But there seems to be more at work here than simply "elite schools educate the most talented young people of their generation."

Rather, it seems likely that the pathways that lead to career success are themselves facilitated by the social resources created for the graduate by his or her university: networks of alumni, the prestige of the degree, and the classmates and their families whom they come to know. The density of elite social networks seems to be a key part of the story; avenues into elite careers are facilitated by these contacts and social advantages. Contacts in government, politics, journalism, business, and Wall Street are richly available to the rising elite university graduate. An elite university provides a great reserve of social capital for the graduate. and this is unrelated to the actual level of achievement and talent that the graduate possesses.

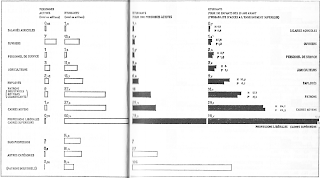

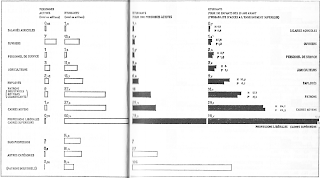

Here are two empirical studies that complement these suspicions -- one in France in the 1960s and the other in the United States in the 1990s. Both studies are interested in essentially the same question: to what extent do universities (French or American) provide equitable opportunities across social groups? To what extent are the universities in these countries effective agents for bringing about greater social equality?

First, France. One of Pierre Bourdieu's earliest works is a study (with Jean-Claude Passeron) of the social inequalities that are reproduced by the French educational system (

Les Héritiers : Les étudiants et la culture

, 1964). Essentially Bourdieu and Passeron provide empirical data from 1961-62 that demonstrate that the population of French university students was highly unrepresentative of the social categories of the larger population. The likelihood of attending university was many times higher for some economic classes than others. Here is a graphic that captures the heart of Bourdieu and Passeron's findings:

In spite of the pre-Pixar graphics, I think Edward Tufte would approve; the graph displays very economically the fundamental relationship that the authors want to highlight in the data. The left panel of the graph represents the sizes of the populations associated with various social groups as well as the number of students whose background stems from the group. The right panel aggregates these data by computing the percentage of students from each who enroll in a university. For children from the humble social categories, including workers and farmers, the likelihood of attending university was very small, ranging from .7% to 3.6%. Higher social categories had substantially greater rates of attendance, ranging from 16.4% for the children of the owners of businesses to 29.6% and 58.5% for the children of lesser and higher civil servants and professionals. From top to bottom, then, the disparity of odds for different social groups is staggering. The children of professionals and high civil servants were 85 times more likely to attend university than hired farm workers, and they were 42 times more likely to attend than the children of blue collar workers. They also look carefully at academic success and choice of professions by the social class of the students' parents -- a perspective which continues through the present. Naturally, these findings are specific to a point in time -- 1961-62. No doubt these disparities have narrowed in the fifty years since Bourdieu and Passeron did this research. But they asked the right questions, and they established a perspective on French education that has continued to guide research in France.

And second, the United States. William Bowen, Martin Kurzweil, and Eugene Tobin provide a careful, empirically detailed and historically nuanced treatment of these issues in

Equity and Excellence in American Higher Education (2005

). One chapter of

Equity and Excellence is particularly relevant to the question here. In "The Elite Schools: Engines of Opportunity or Bastions of Privilege?" the authors consider a large data set of admissions and outcomes at 19 selective colleges and universities (94). It is a fascinating analysis.

Their conclusion is a nuanced one:

By providing an increasingly straight path to entry and graduation for academically talented students from all socioeconomic strata, these prestigious institutions are fulfilling their historical promise to serve as "engines of opportunity." On the other hand, the disproportionately large number of graduates of these schools who come from the top rungs of American society indicate that they also remain "bastions of privilege." Vigorous recruiting notwithstanding, the applicant pools of these schools contain only a small number of well-prepared students from families of modest circumstances. This is the "controlling reality." (135)

They also find that students from disadvantaged socioeconomic origins are severely underrepresented in the elite institutions included in their study (parallel to the Bourdieu-Passeron findings):

Students whose families are in the bottom quartile of the national income distribution represent roughly 10 to 11 percent of all students at these schools, and first-generation college students represent a little over 6 percent of these student populations.... Both groups are heavily underrepresented at the institutions in our study. ... When we combine the two measures of SES, and estimate the fraction of the enrollment at these schools that is made up of students who are both first-generation college-goers and from low-income families, we get a figure of about 3 percent. Nationally, the share of the same-age population who fell into this category was around 19 percent in 1992, making this doubly disadvantaged group even more underrepresented than students with just one of the two characteristics. (98)

This looks at the issue from the point of view of "probability of attendance" -- the focus of the Bourdieu-Passeron analysis. What about the outcomes of students from different socioeconomic groups who have successfully graduated from the elite institutions that Bowen et al survey? Does SES status influence career success? Bowen and his colleagues find that it does. First, a very crude measure: "The average income in 1994 or 1995 of a former student from the bottom income quartile was over $67,000; former students from the middle two quartiles had average incomes of between $73,000 and $75,000; and those from the top quartile had average earnings of nearly $86,000" (123). And an even more telling statistic when it comes to the sociology of American elites: "Just under 2% of former students from the bottom income quartile had a very high income 15 years out of college, while almost 6 percent of former students from families in the highest income quartile were themselves already in the top income category" (123). So socioeconomic background makes a difference all the way through; high SES graduates are three times as likely to have very high income than their equally qualified classmates from low SES circumstances. This certainly suggests that elite universities fail in the democratic ideal of leveling the playing field for persons of talent.

So it isn't really possible to answer the simple question with a simple answer: do modern educational systems in democracies level inequalities or increase inequalities? It would seem that they do some of both; they provide access to disadvantaged people who can then leverage success for themselves and their families, and they also create mechanisms of recruitment into elite organizations that are anything but egalitarian.

Posted in:

Posted in: